Chapter 11: Wildfires

INTRODUCTION

Wildfires are a natural phenomenon that have occurred for many millions of years. While they have many ecosystem benefits, they also pose a threat to human habitation that is increasingly moving into the urban-wildland interface. Human changes to landscapes, including wildfire suppression, have reduced the natural fire cycle and increased the probability of large, hot, and damaging fires that can reduce ecosystem functioning for many years. In this chapter we will explore what controls wildfire spread, how humans can mitigate and prepare for wildfires, and the human and ecosystem impacts of wildfires.

Wildfires are a natural phenomenon that have occurred for many millions of years. While they have many ecosystem benefits, they also pose a threat to human habitation that is increasingly moving into the urban-wildland interface. Human changes to landscapes, including wildfire suppression, have reduced the natural fire cycle and increased the probability of large, hot, and damaging fires that can reduce ecosystem functioning for many years. In this chapter we will explore what controls wildfire spread, how humans can mitigate and prepare for wildfires, and the human and ecosystem impacts of wildfires.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

The goals and objectives of this chapter are to:

The goals and objectives of this chapter are to:

- Describe the causes of wildfire ignition and spread.

- Explain the positive and negative impacts of wildfires.

- Describe how mitigation can reduce wildfire risk.

- Explore the role of wildland firefighters in fire management.

Introduction to Wildfires

|

TYPES OF WILDFIRES

The three main types of wildfires, as described by the National Park Service are: Ground fires—which burn organic matter in the soil beneath surface litter and are sustained by glowing combustion. Surface fires—which spread with a flaming front and burn leaf litter, fallen branches and other fuels located at ground level. Crown fires—which burn through the top layer of foliage on a tree, known as the canopy or crown fires. Crown fires, the most intense type of fire and often the most difficult to contain, need strong winds, steep slopes and a heavy fuel load to continue burning. |

ECOLOGICAL EFFECTS

Read pages 1-3 in the USDA report below about the basic impacts of wildfires and the ecological effects:

Read pages 1-3 in the USDA report below about the basic impacts of wildfires and the ecological effects:

The Fire Environment

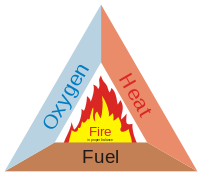

For wildfires, this triangle is sometimes modified to include the specific factors important for fires in wilderness lands namely:

Topography, while easy to analyze with topographic maps, is a challenging factor for wildfire spread. First, fire, being hot, tend to move upward, and therefore will move up slopes at a much faster speed than down slopes. Additionally, the steepness and aspect of slopes will determine the type and spacing of vegetation growing. Wildfires burning in very complex topography are challenging to forecast and pose a particular danger.

- Fuel

- Topography

- Weather

Topography, while easy to analyze with topographic maps, is a challenging factor for wildfire spread. First, fire, being hot, tend to move upward, and therefore will move up slopes at a much faster speed than down slopes. Additionally, the steepness and aspect of slopes will determine the type and spacing of vegetation growing. Wildfires burning in very complex topography are challenging to forecast and pose a particular danger.

|

|

FIRE WEATHER

Weather is critical in forecasting both the likelihood that a wildfire will start, as well as the behavior of a fire once it has started. The key weather variables that impact fire are:

|

Meteorologists and firefighting personnel can assess these conditions in the field using existing surface weather stations, with temporary weather stations, and with handheld weather stations. Forecasts of these conditions are created by local offices of the National Weather Service and communicated to firefighters and emergency managers in the field. On large fires, and Incident Meteorologist from the National Weather Service is assigned and sent to the fire location to provide detailed and up to date weather information to personnel in real time.

However, in many cases the fire itself can create different weather conditions. Additionally, the topography around the fire can create weather. These, changes in conditions happen on very small scales and are not able to be forecast by meteorologists. Therefore, it is important for wildland firefighters to have a basic understanding of fire weather, so they can assess changing situations in the field and modify their activities to stay safe.

However, in many cases the fire itself can create different weather conditions. Additionally, the topography around the fire can create weather. These, changes in conditions happen on very small scales and are not able to be forecast by meteorologists. Therefore, it is important for wildland firefighters to have a basic understanding of fire weather, so they can assess changing situations in the field and modify their activities to stay safe.

Impacts of Wildfires

WILDFIRE THREATS

Read the USGS report below to explore the threat of wildfires in the United States:

Read the USGS report below to explore the threat of wildfires in the United States:

Fighting Wildfires

|

MITIGATING THE THREAT

Wildfire mitigation has three main components:

|

|

|

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) recommends the following steps to create defensible space and prepare homes within wildfire hazard areas:

|

|

|

WILDLAND FIREFIGHTERS

Fighting wildfires is a dangerous and physically demanding job, which requires extensive training. This training has three main facets.

|

|

10 Standard Firefighting Orders

Fire Behavior 1. Keep informed on fire weather conditions and forecasts. 2. Know what your fire is doing at all times. 3. Base all actions on current and expected behavior of the fire. Fireline Safety 4. Identify escape routes and safety zones and make them known. 5. Post lookouts when there is possible danger. 6. Be alert. Keep calm. Think clearly. Act decisively. Organizational Control 7. Maintain prompt communications with your forces, your supervisor and adjoining forces. 8. Give clear instructions and be sure they are understood. 9. Maintain control of your forces at all times. If 1-9 are considered, then... 10. Fight fire agressively, having provided for safety first. |

Eighteen Watch Out Situations

|

Case Studies

|

YARNELL HILL FIRE

A lightning storm ignited a wildfire on June 28, 2013 in a desert area northwest of Phoenix, AZ. As the fire grew nearby towns were evacuated and the Granite Mountain Hot Shots crew arrived to aid in fire suppression and protection of the nearby towns. On June 30, 2013, while retreating toward the town of Yarnell, 19 of the firefighters were overtaken by the flame front. They deployed their fire shelters, but all 19 succumbed to the heat and flames. The accident was partly caused by outflow winds from a thunderstorm to the northwest, which increased fire movement dramatically and created dangerous fire conditions. More detailed information and accounts from this tragedy can be explored HERE. |

|

|

MILFORD FLAT FIRE

The Milford Flat Fire was the largest wildfire in Utah history, 363,000 acres, and started from dry thunderstorms on July 6, 2007. Milford Flat is an area in central Utah north of the town of Milford and west of the I-15 corridor and the towns of Fillmore and Kanosh. While the wildfire itself caused little damage to infrastructure, post-fire rehabilitation desertified the area and created a large source of dust for many years. Strong winds from the south ahead of approaching storm systems lofted dust from the fire scar and transported north to the population centers along the Wasatch Front of Utah and the Wasatch Mountains. These dust storms are a hazard to transportation and human health, but also increase the melt rate of mountain snowpacks, by creating a darker surface, which absorbs more solar radiation. |

RESOURCES

Firewise Communities, http://www.firewise.org/

National Interagency Fire Center, https://www.nifc.gov/

Ready.gov: Wildifres, http://www.ready.gov/wildfires

USDA, Wildfire, Wildlands, and People: Understanding and Preparing for Wildfire in the Wildland-Urban Interface, January 2013

http://www.fs.fed.us/openspace/fote/reports/GTR-299.pdf

USGS, Wildfire Hazards--A National Threat, February 2006

http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2006/3015/2006-3015.pdf

Utah Fire Info, http://www.utahfireinfo.gov/

Firewise Communities, http://www.firewise.org/

National Interagency Fire Center, https://www.nifc.gov/

Ready.gov: Wildifres, http://www.ready.gov/wildfires

USDA, Wildfire, Wildlands, and People: Understanding and Preparing for Wildfire in the Wildland-Urban Interface, January 2013

http://www.fs.fed.us/openspace/fote/reports/GTR-299.pdf

USGS, Wildfire Hazards--A National Threat, February 2006

http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2006/3015/2006-3015.pdf

Utah Fire Info, http://www.utahfireinfo.gov/